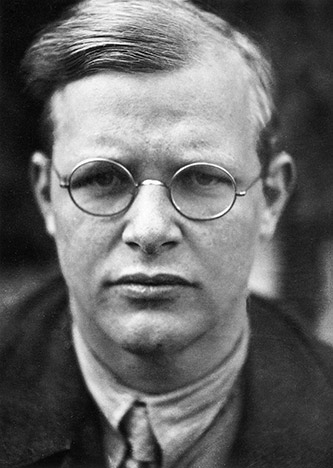

Dietrich Bonhoeffer opposed the Führer cult — a cult of personality replete with loyalty oaths et al — since its inception in 1933. Twelve years later, on this day in 1945, the Nazis hanged him at the Flossenbürg concentration camp, three weeks before the Führer committed suicide. He was thirty-nine-years old. The following excerpt is taken from Bonhoeffer, by Stephen Plant (London: Continuum, 2004, pages 28–34). It briefly sketches his last years as well as his end:

* * *

In 1938 the dark shadow of Nazi ambitions spread over Germany and over Europe. In March German troops marched into Austria, whose Government instructed the Austrian Army to offer no resistance. Austrians greeted the Anschluss with widespread enthusiasm. Throughout the year Hitler skilfully manipulated the European powers. Possibly blinded to the true nature of Nazi objectives, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain agreed Hitler’s aims at a conference in Munich, claiming the agreement guaranteed ‘peace in our time’. Under this agreement Germany annexed the Sudetenland across its south-eastern border ostensibly to protect the interests of the German speakers there; by the following year Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia had become German protectorates. . . . In March 1941 he was forbidden to publish because of his ‘subversive activities’. In order to avoid conscription and to situate himself within the anti-Nazi conspiracy, Bonhoeffer became a civilian member of the German Military Intelligence, who justified his role on the basis that his international ecumenical contacts yielded useful information. It was a strange moment to join the conspiracy. Before the war many German generals had treated Hitler’s predictions of rapid success with scepticism: with Corporal Hitler proved right so spectacularly the possibility of a military coup for the moment passed. Removing Hitler would be a long game.

Upon the outbreak of war a kind of rapprochement took place between the churches and the Nazi state, as many who had previously doubted the regime patriotically put themselves behind the war effort. For their part, the Nazis were content to bide their time in relation to Christianity. Josef Goebbels, Hitler’s ‘Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda’ recorded in a diary entry in 1939 the true nature of Nazi policy towards the churches in wartime:

The best way to deal with the churches is to claim to be a positive Christian . . . the technique must be to hold back for the present and coolly strangle any attempts at impudence or interference in the affairs of the state . . . He [Hitler] views Christianity as a symptom of decay. Rightly so. It is a branch of the Jewish race.

The policy, in other words, was to permit a certain freedom to the churches during wartime with the intention of crushing them when victory was complete. Yet the war also revealed the criminal character of the Nazis more clearly, and this resulted in the one confrontation of church and state that had genuinely successful results. This was when, after war began, a euthanasia programme was initiated to kill off people considered an unnecessary drain on the nation’s resources in war: these included the mentally disabled, the severely mentally ill, those with extreme dementia or epilepsy, as well as some with physical disability. The method was to order a transfer of a patient or group of patients to another unnamed institution. Soon after a note would inform relatives that the patient had died. Church-based institutions carried out a good deal of care and treatment for people in these ‘categories’, and it was apparent, even to the most credulous, that a large number of people were being murdered. Opposition to the programme had evidence that was difficult to refute; confronted in this way the state called off the programme at the end of 1941, shortly before the Wannsee Conference, which initiated the ‘Final Solution’ of the Jewish ‘problem’.

Bonhoeffer’s life as an agent of the Military Intelligence left him plenty of time to think, and the period from mid-1940 to his arrest in 1943 was theologically among the most fruitful of his life. Bonhoeffer turned his attention once more to ethics, which enabled him to integrate theology with the events in which he was engaged; the results, fragmentary and brilliant, are discussed in Chapter 7. His strengthening theological hold on daily life corresponded with a momentous personal development when in January 1943 Bonhoeffer became engaged, secretly at first because she was only eighteen years old, to Maria von Wedemeyer. Maria’s grandmother was one of Bonhoeffer’s most ardent supporters during his Directorship of the seminary and the pastorates; her father and brother were army officers killed in the war. It was an unusual alliance; intense, life-giving and strained by the war and the conspiracy, his involvement in which Bonhoeffer did not fully disclose. On behalf of Military Intelligence Bonhoeffer travelled three times to Switzerland, twice to Sweden, and once to Norway during 1941 and 1942. But in spite of all the care and caution taken by the conspirators within Military Intelligence, tracks had been left. In 1942 the Gestapo began investigating Abwehr activities. Von Dohnanyi received a warning that his telephone and post were under surveillance; a routine request for a visa for Dietrich went unanswered. On 5 April 1943 Bonhoeffer, who was working on his ethics at his parents’ house in Berlin, telephoned his sister Christine von Dohnanyi and a stranger answered. Dietrich knew at once that the man was a Gestapo officer. He cleared his desk and went next door to his sister Ursula’s and ate a good meal. Shortly after his father came to tell him that ‘there are two men wanting to speak to you upstairs in your room’.

“Silence in the face of evil is itself evil: God will not hold us guiltless. Not to speak is to speak. Not to act is to act.” — Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Tegel was a military interrogation prison and though a civilian, Bonhoeffer was held there as a member of the Abwehr. Bonhoeffer’s first days there were grim. Mentally he had prepared himself for this moment, but his isolation and the conditions penetrated his soul. He was unaccustomed to incivility and brutality. At this early stage his investigators did not suspect his involvement in a plot to assassinate the Fuhrer. When he was finally charged, it was with ‘subversion of the armed forces’ because he had ‘evaded’ conscription and helped at least one other to do so. The Abwehr was also under investigation for its role in an operation, in which Bonhoeffer was personally involved, smuggling Jews to Switzerland. Bonhoeffer’s relative Lieutenant General Paul von Hase — who would later pay with his life for his own involvement in the resistance — was military governor of Berlin and visited him in the prison with several bottles of wine and pointedly talked and laughed with his nephew. After the visit Bonhoeffer was treated with more respect. As the months of Bonhoeffer’s imprisonment wore on he adapted to the routine. His family brought him food, clothes, books and tobacco. He exercised, read extensively and tried his hand at writing poetry, a play and a novel. A sympathetic guard smuggled letters in and out of his cell; by this avenue we have the correspondence published after the war as Bonhoeffer’s Letters and Papers from Prison. In prison Bonhoeffer was as much in danger from allied bombing as from the investigation; he lost patience with others’ fear — and he lost a friend to a direct hit.

In July 1944 an assassination attempt was made on Hitler’s life. Bonhoeffer knew it was coming and his smuggled letters reflect both his patience and impatience to know the outcome. In October 1944 evidence came to light linking him with the attempted assassination. He was transferred to the Gestapo prison in Prinz Albrecht Strasse and his links with family and friends were abruptly ended. In February 1945 Bonhoeffer was moved again, this time to the Buchenwald concentration camp, then to Regensburg and Schonberg. He developed relationships with those who shared his confinement and journeys. One, British officer Payne Best, later recalled that Bonhoeffer never complained but was, rather, ‘quite calm and normal; seemingly perfectly at his ease . . . his soul really shone in the dark desperation of our prison’. With a Soviet prisoner, Kokorin — a nephew of Molotov — Bonhoeffer learned Russian in exchange for lessons in the rudiments of Christian theology. On the Sunday after Easter a group of fellow prisoners asked Bonhoeffer to conduct a service for them. At first he was reluctant in deference to the Catholics and Atheists among the group, but when Kokorin approved, he agreed. He explained the texts for the day ‘With his wounds we are healed’ (Isaiah 53:5) and ‘Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! By his great mercy we have been born anew to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead’ (1 Peter 1:3). When news spread to other groups that he had led worship, they wanted him to repeat it for them, but there was no time. A call came for ‘Prisoner Bonhoeffer’. He knew what it meant and wrote his name and address in a book he had with him as evidence of his final movements for his family. He asked Payne Best to pass a message to George Bell: ‘this is the end — for me the beginning of life’.

Bonhoeffer was transferred to Flossenbürg concentration camp. A personal order from Hitler had condemned him a few days earlier and had now caught up with him. During the night Bonhoeffer and others from the Abwehr including Admiral Canaris and Brigadier General Oster were summarily tried. At dawn they were ordered to undress. The SS camp doctor — present to certify death — later reported that before he complied Bonhoeffer knelt and prayed. At the gallows he again prayed before composedly climbing the steps. The bodies and possessions of those executed were burned. His brother-in-law Hans von Dohnanyi was killed the same day at Sachsenhausen; on 23 April his brother Klaus and brother-in-law Rudiger Schleicher were executed. On 30 April Adolf Hitler did what the conspirators had failed to do and ended his own life.

* * *

A valuable lesson.

A great hero. Thank you for honoring his life. We should all admire his willingness to speak out and act against evil in the face of all most certain death.

Rose Huskey

Incidentally, Bonhoeffer was also a celibate gay who lived with and shared a bank account with his best male friend… See how the Dougie likes that…